Following the exhibition at the King’s College London Anatomy Museum 2-3rd February, the Narrating Plasticity exhibition moved to the Inigo Rooms for another week of public display…

Over Friday 2nd and Saturday 3rd February, we welcomed over 300 visitors to the Narrating Plasticity exhibition at King’s College London!

On Friday, visitors attended the exhibition for a drinks reception, a premier of the project film , and a Q&A with project coordinator Benjamin Dalton and collaborators Amanda Doidge and Dr Sandrine Thuret’s team of neuroplasticity researchers from the Maurice Wohl Clinical Neuroscience Institute.

Visitors represented a diverse range of backgrounds, from philosophy, French studies, the arts, medicine, education, politics, and many other areas. This lead to such fertile discussion across boundaries, with a huge range of different reactions to the project and ideas for future collaboration!

Do not hesitate to get in touch with coordinator Benjamin Dalton if you have any reactions or photographs to share, or if you have ideas for how Narrating Plasticity could develop further into the future!

The day that ceramicist Amanda Doidge and philosophy researcher Benjamin Dalton stepped foot in the laboratory of the Maurice Wohl Neuroscience Institute

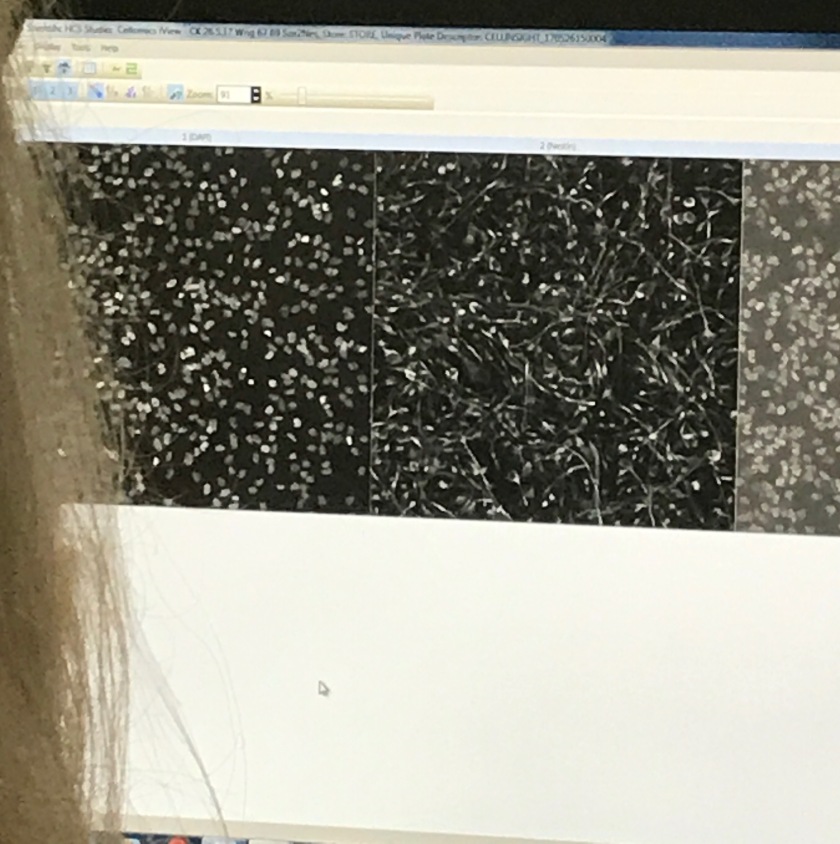

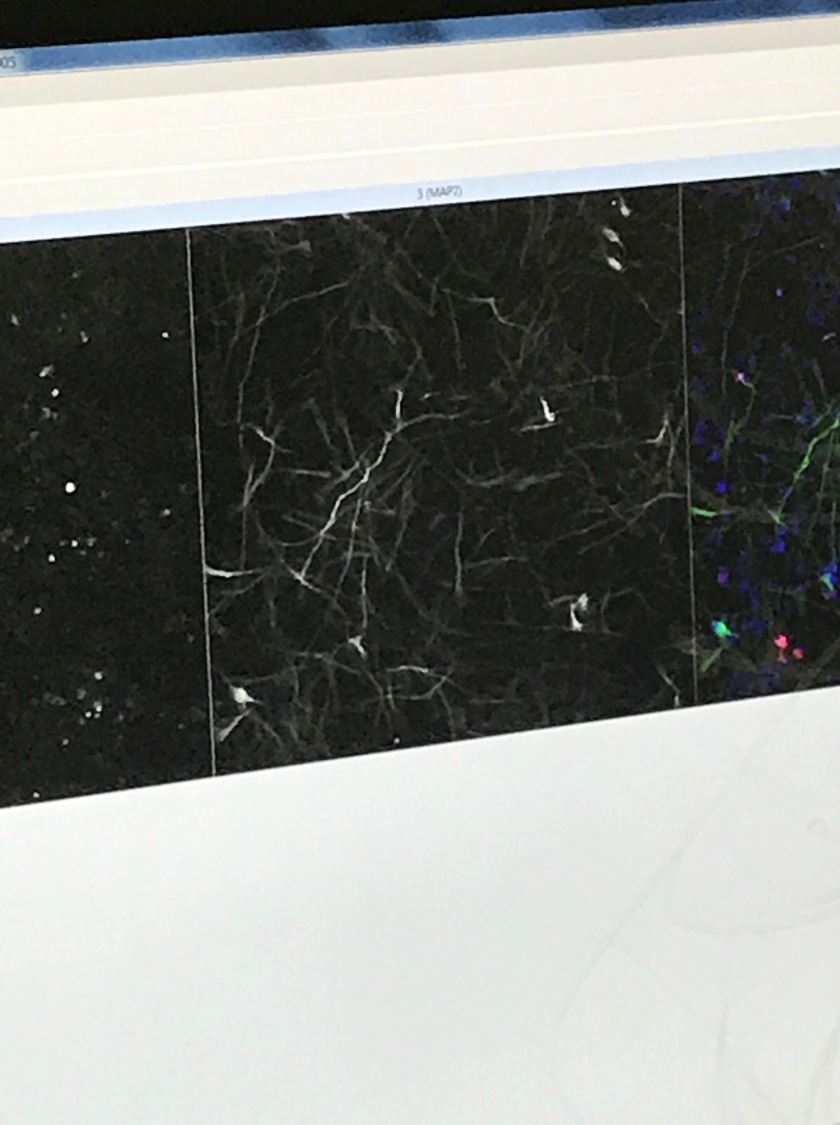

Many conversations were had when Amanda and I spent the afternoon with Dr Sandrine’s team of neuroplasticity researchers at the Maurice Wohl Clinical Neuroscience Institute. Questions ranged from the scientific to the personal, from the artistic to the political. We looked down microscopes, studied images of neurogenesis, observed stem cell cultures, and talked ceramics.

Questions included:

How do scientists measure plasticity?

What does the concept of “form” mean to science?

Why does life have to take “form”? Is life possible without “form”?

Does (neuro)plasticity only ever describe healthy, helpful processes of evolution and development, or can “bad”, pathological processes also be described as “plastic”?

Cups, Trauma, and Heraclitus: Recalling my very first visit to meet the ceramicist Amanda Doidge at her workshop in Walthamstow

I first emailed the ceramicist Amanda Doidge to see if she would be interested in collaborating on the Narrating Plasticity project on a beautiful summer’s day in 2016. I had been fascinated by her dark, destructive ceramics and her interest in arts and science collaboration. I clicked send and went back out into my garden in Wolverhampton to listen to Girls Aloud in the sun, not expecting to be contacted for a week or two.

Just ten minutes later Amanda called, asking if I would like to visit her in her studio in Walthamstow to discuss the project. I was very excited.

Two weeks later and I was on the tube to Walthamstow Central. Amanda showed me straight to her studio where her art work was being displayed as part of the E17 Art Trail.

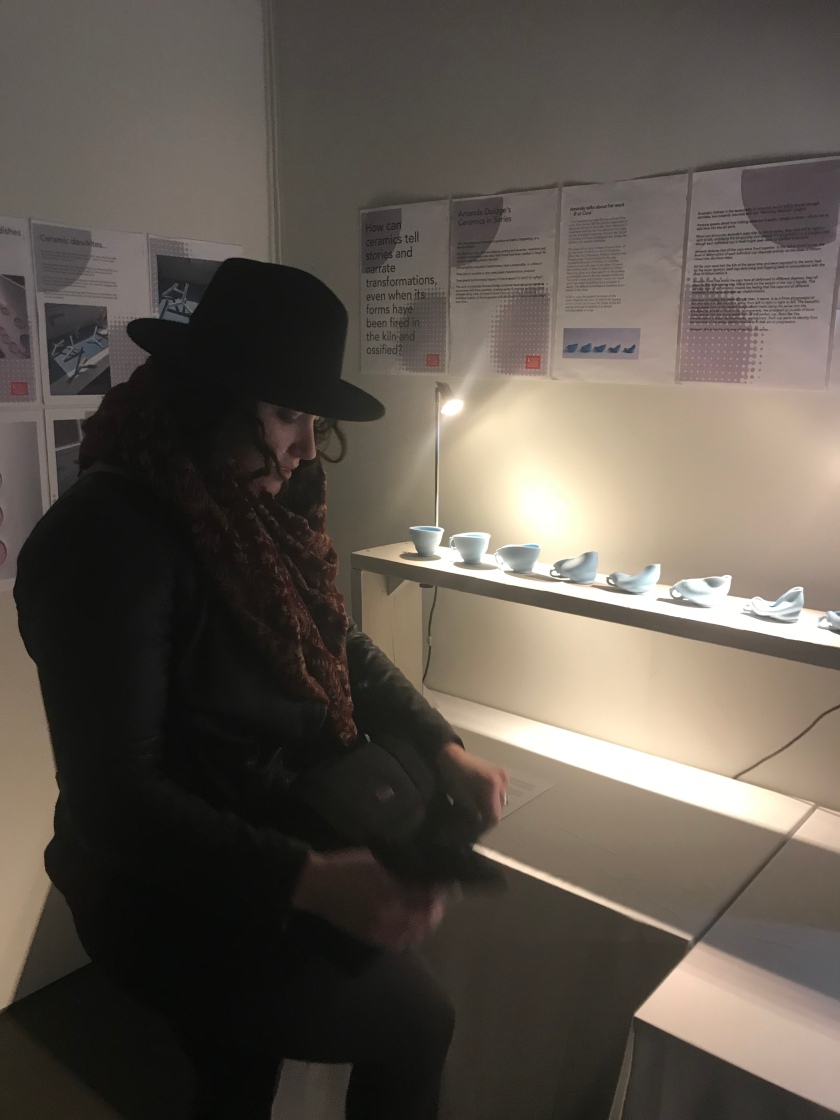

Amanda told me that she was interested in series because she wanted to bring her ceramics to life somehow. Series of cups told a story. Amanda told me she liked how a series could either be a multitude of different cups, or display the same cup at different moments in its transformation.

To put the ceramics in series introduces the element of time into the ceramics.

In Kill or Cure, the cup appears to deform over a period of time, falling back under the weight of its handle. Each cup had been fired with an increasing amount of lithium in it, with the higher doses causing higher levels of deformation.

Amanda and I discussed what it meant to take one cup out of the series and look at it in isolation: it doesn’t even look like a cup, you are seeing it out of context, you do not know what has happened to it to produce that form.

In this way, seeing a cup in isolation is like meeting someone for the first time, be that on the street, or in a clinical setting when a doctor is trying to determine the history of a patient, or the development of a problem: you do not know what has preceded that form, or where that form will go next.

“The exploding glazes are exciting,” Amanda tells me. “But they won’t do. We want our apoptosis controlled!”

What is a narrative? What kind of stories can be put into narrative? What kinds of narratives do plastic things create – a sculpture, a frieze, or the plastic brain – when they are no longer bound to linear time?

Following my brain surgery and my week long stay in the King’s College Hospital neurology ward, I began to wonder how people transformed following brain injury or surgery might be able to narrate and communicate their transformations to clinical teams and loved ones.

As we discussed previously, neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s capacity to transform and change form throughout its lifetime, modulating neural subjectivity in response to life events and traumas; however, as the philosopher Catherine Malabou argues, plasticity is not a merely positive capacity for adaptation but also a dark creativity in which the brain can take the plastic form of a trauma it encounters, thus rendering someone unrecogniseable.

If (neuro-)plastic transformations had occurred in these people’s brains and lives, and these plastic changes defied the usual chronologies or logics of normative narrative structures, then their narratives would also have to be plastic.

What is a plastic narrative?

For inspiration as to what a “plastic narrative” might be, I turn again to the philosopher Catherine Malabou’s work Ontology of the Accident (2009).

In this book, Malabou argues that we must not only narrate “good” or “positive” plasticity, but indeed “destructive plasticity”. In other words, instances of neural trauma or pathology should not be seen as glitches or interruptions in “healthy” plasticity, but as valid plastic creations in their own right. Indeed, Malabou seems to argue, the powerful negativity of destructive plasticity seems to be central to the logic of all plastic creation and formation. A blown apart sculpture is still a sculpture, and a traumatised brain is still a brain.

Malabou suggests that, until now, cultural production and neuroscientific endeavour alike have been preoccupied with “good” plasticity, and therefore do not yet seem to have tools or forms necessary for communicating destructive plasticity.

Metamorphoses in literature, for instance, predominantly portrays transformation as a positive and helpful occurrence. Malabou reads Ovid’s Metamorphoses as a series of transformations which help the subject who is transforming. Daphne, for instance, turns into a tree in order to outrun Phoebus, and remains very much Daphne despite having taken the form of a tree. Likewise, in Kafka’s famous Die Verwandlung in which the protagonist Gregor Samsa wakes up to find himself transformed into a beetle, Gregor is still able to think and feel like Gregor despite his bodily metamorphosis. For this reason, Malabou argues, these are not true plastic narratives as they are unable to articulate the truly destructive potentiality of plastic transformation.

A plastic narrative, then, needs to be able to communicate transformation whilst retaining the radically of the temporal and formal disruptions and destructions at their core.

Amanda Doidge introduces me to her first experiment with “destructive plasticity” or “destructive creation” in the form of a series of Petri dishes made with mutant glazes!

The following explosive, exploded, destructive and destroyed Petri dishes are the results of Amanda’s initial meditations on “destructive plasticity” for the project.

Amanda sends me a cooly dramatic email just before she went away on holiday: “Hi Ben, these are some glaze tests of crawling and crazing glazes. A lot of them exploded in the kiln as they cooled down. I am going away tomorrow. Amanda.”

The results are fantastic: cracked, greenish, pulled apart Petri dishes, some of which bubble and churn like creme brûlées or curdled milk, and others which crack into harsh geometrities and matrices like a the mudcrack floor of a desert.

When Amanda had explained to me the idea of the self-destructing Petri dishes, she told me that the glaze would be the detonator. Looking through a recipe book of glaze mixes, and pointing to a shelf full of labeled chemicals and elements in jars (Aluminum, flint, LiCO3, Magnesium Carbonate, etc…), Amanda had told me her aim was to “do everything wrong” in preparing the glaze mixtures.

Amanda had got the idea for the Petri dishes from a visit to the neuroscience laboratory at the Maurice Wohl Clinical Neuroscience Institute when we met Dr Sandrine Thuret’s team for the first time. Amanda had become interested in the successions of the simple, clinical forms in series used for looking at stem cells. Creating explosive Petri dishes in the kiln would be a way of thinking the tension between the clinical inertia and prophylaxis of the Petri dishes, and the dynamic, destructive-creative potential of the stem cells.

Amanda prepared her Petri dishes for the kiln like little bombs. Whilst the kiln is usually the step in the ceramic produce in which form is solidified, ossified, and confirmed, Amanda’s Petri dishes explore the kiln as the site at which form is destroyed, pulled apart, and a form is created out of the destruction of form.

Amanda and I have been reading the philosopher Catherine Malabou‘s theories of of “destructive plasticity” together, looking in particular at her works What to do with What To Do With Our Brain? (2004), Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity (2009), and The New Wounded: From Neurosis to Brain Damage (2009).

In these works, Malabou looks at people’s brains who have been irrevocably transformed through injury or neuropathology, her personality and selfhood becoming suddenly completely different from the person they had been before the event. Malabou argues that these transformation are not the opposite of form, they are not interruptions in plasticity, but they are themselves a form of plasticity: a form is always created when an old form is destroyed, a form of destruction.

I am not sure how much Malabou’s “destructive plasticity” is playing a part in Amanda’s thinking of the Petri dishes at this moment, or whether Amanda’s own “destructive plasticity” is something altogether different and divergent. I am excited to see where this will lead!

Ceramicist Amanda Doidge creates series of ceramics, introducing small differences between each individual item, adding evolution and temporality in her plastic (de)formations.

How does plastic art represent or produce an event, a happening, or a transformation?

Can the plastic arts – such as sculpture, pottery and ceramics – transform and express transformation even after their forms have been ossified or fixed, for example after being fired in the kiln?

Does plasticity and plastic transformation have a temporality, or a history? What kind of narrative or story does plastic transformation produce?

Does plastic transformation happy in time or space? Or both? Or neither?

The work of ceramicist Amanda Doidge comprises fascinating and surprising engagements with these questions.

Amanda Doidge: Ceramics, temporality, event

Describing her recent creations in experimental ceramics on her website, Amanda says:

“I am fascinated by how life has evolved from rock. How can we tell the precise stage when it becomes life and is no longer ‘just’ chemistry? I have been looking into the elements that make up clay and glaze materials, that are also found in humans and have a biological role. Some, like Lithium, are used as medicines.

This piece kill or cure is made of bone china, all the elements of which are found in humans: Silica, Alumina, Potassium, Sodium, Calcium and Phosphorous. I have included in the clay increasing amounts of Lithium. In ceramics, Lithium is normally used in the glaze. It lowers the melting point of silica. In medicine Lithium has to be given at a dose specific to the patient, and patients have to be very closely monitored. Too small a dose and it doesn’t work, too much and it can cause everything from paralysis to death. The difference between a medicine and a poison is the dose. In kill or cure, the gradual increases of the ‘dose’ illustrate the story of where the tipping point is. If you do not see the whole series but see the final cup in isolation it is almost unrecognisable as a cup.

The series of cups below is also made of bone china. I have made a mould and carved into it – repeatedly carving into the plaster mould and recasting the clay until gradually the cup disappears, consumed by the rock. Displayed the other way around, it seems as though a cup is emerging from the rock. I was inspired by a story about Michelangelo, who was asked by a small boy why he was chipping away at a piece of marble: his answer was ‘because there is an angel inside.’”

Change and transformation in series: A linear progression?

Upon meeting Amanda, I knew that her way of working and thinking plastic transformation and deformation through ceramics would be perfect for the “Narrating Plasticity” project.

Amanda’s way of producing bone china cups in series, with minute differences and transformations between the cups, struck me as a way of putting temporality in ceramics.

When you encounter Amanda’s cups side by side in series, they read left to right or right to left, mobilising the temporality and kenesis of a progression or a change, even though each individual cup in itself might seen static or ossified in its form.

Amanda stresses that all the cups were fired together. In the Kill or Cure? series, the level of deformation of each individual cup depends entirely on the dose of lithium mixed into the bone china.

All the cups went into the kiln at the same time and were exposed to the same heat for the same duration, each cup deforming and flopping back in concordance with the dose of lithium within it. Amanda notes that whilst the cups have all deformed to different degrees, they all seem to flop in the same way, falling back on the weight of the cup’s handle. This unifying logic of deformation creates the feeling that the cups are all different moments in the same narrative arc of deformation.

One way of reading this series of cups, then, it seems, is as a linear progression of transformation or deformations, either from left to right or right to left. The beautiful, recognisable form of the perfect cup gradually melts along the series into the smudged up puddle of bone china, or conversely, the smudged up puddle of bone china evolves into the recognisable form of the perfect cup. Read like this, transformation is linear, developmental, evolutionary. Each cup gains its identity from the narrative of the series, identity evolves as a clear arc or progression.

However, this is not the only way of reading the series.

Taking the form out of the series

The cup pictured below is Amanda’s favourite cup in the series.

When we have finished looking at the cups in series, Amanda picks one of the cups out and places it on a different table in isolation.

“Look at it,” she says. “You probably wouldn’t know it was a cup.”

Taken out of context, the cup loses its narrative arc, its logic or history of transformation. It is rid of its linear, helpful temporality.

We don’t know quite where the cup’s deformations are coming from, or where they are going. We don’t know what the cup was “before”. Has its function as a cup changed? Is it still a receptacle? Is it still a form?

Is there still temporality even though this temporality has been taken out of its linear progression? Is there a narrative of this transformed or evacuated temporality?

Talking through the initial brief of the “Narrating Plasticity” project with Amanda, the image of the transformed cup in isolation seemed particularly resonant. We talked about the neuro-ward, and how clinical teams will encounter a patient completely out of context. This patient will sometimes have undergone changes to their brain that will have rendered them very different to the person they were “before”, and yet taken out of context, the story of that change is very difficult to communicate, or indeed becomes itself fragmented, or is erased entirely.

Over the course of this project, from the transforming cups in the series onwards, we hope to think about ways of communicating and narrating plastic transformation where recourse to linear temporality and developmental narrative arcs are no longer possible.

Before we begin, what actually is

“plasticity”? Indeed, is there such a thing as a unified concept of plasticity, or are we always talking about various different “plasticities” in the plural?

[Go to official “What is plasticity?” blog page]

A plastic world?

The words “plastic” and “plasticity” come from the Greek plassein meaning “to mould”.

At its most fundamental, then, plasticity as a material characteristic names a certain malleability: plastic things can be moulded, plastic things take form.

Today, of course, the meanings and the forms of plasticity have proliferated, the concept of plasticity itself becoming plastic, mutating and taking different forms across various different contexts.

It might be more fitting to talk of plasticities in the plural; this project, Narrating Plasticity, seeks to open dialogues between these different plasticities, questioning the origins and futures of the concept(s).

We talk of the plastic arts – the three-dimensional creations of artists manipulating material into their desired forms.

In the neurosciences, and more and more in popular science knowledge, plasticity, or more precisely neuroplasticity, has come to name the ability of the brain to change and restructure its own synaptic form over the course of a lifetime, transforming to reflect the impact of personal experience or reorganise and regenerate following trauma or injury.

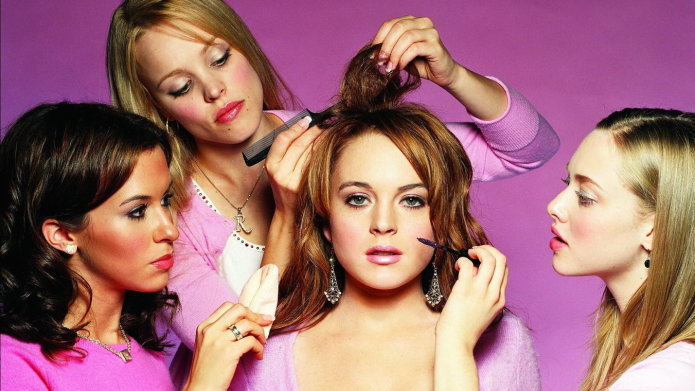

The world in which we live is also, of course, increasingly populated by plastic materiality and logics. Our furniture is plastic. Our toys are plastic. Our clothes are plastic. Our money is plastic. We are 3D printing our bridges. We are changing our bodies with plastic surgery. The mean girls of Mean Girls are “the Plastics”.

PLASTIC ART

“Plastic arts” refers primarily to art forms that result from the manipulation of plastic materials into any given form. These art forms might include sculpture, pottery, ceramics, etc.

Less commonly, “plastic arts” can refer the visual arts more broadly (painting, photography, film, etc.) in order to distinguish these art forms from the written arts, such as poetry or music.

The question of the specificity of plastic art forms as distinct from written works has been a central debate in art theory and history.

Famously, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing argues in his work Laocoön: An Essay upon the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1766) that plastic art and poetry can capture the same narratives, events, or ideas, but in very different ways.

Lessing looks at two different artistic interpretations of the Greek mythological tale of the Trojan priest Laocoön being murdered by giant sea serpents alongside his sons as punishment for having angered the gods. Lessing compares Virgil’s account of Laocoön’s death in The Aeneid (70BC – 19BC) to the sculpture of the Laocoön (200 – 20BC, currently on display at the Vatican Museum).

Lessing argues that whilst the sculpture represents the narrative event in space, the poetry represents the narrative in time. He also argues that whilst the poetry is able to convey the true horror of the situation, the sculpture “[strives] to attain the greatest beauty under the given conditions of bodily pain.”

Modern art continues to celebrate plastic form in new and innovative ways, from the violent horrors of Hans Bellmer to Marcel Duchamp’s (in)famous work “Fountain” (1917).

The explosion of plastic materials, or simply “plastics”, as we know them today from the 1930s onwards – low cost, synthetic, moldable polymers – also of course massively influenced and continue to influence the plastic arts as a material capable of reproduction on an industrial scale.

PLASTIC NEUROSCIENCE

In neurobiology, plasticity or neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s capacity to adjust and transform throughout life, dynamically changing synaptic form in response to experience or injury.

Before the 1970s, it had typically been thought that the structures and connections of the adult brain remained fixed and static. However, since then studies in the mutability and adaptability of the human brain have proliferated.

In 1964, anatomist Marian Diamond published a study on the changes that occur in a rat’s brain in response to its environment. This is widely argued to be some of the first scientific evidence of neuroplasticity.

Since then, studies have shown how the brain can recover following strokes or other pathologies and injuries, “healthy” parts of the brain taking over from damaged parts, reconfiguring and redistributing cerebral tasks across new or transformed connections.

A study conducted on London taxi drivers showed the section of the brain associated with spatial memory in the hippocampus to be greatly more developed than controls.

It should be noted that even in the field of neuroscience, the term “neuroplasticity” has many different, and sometimes even antithetical, applications.

In their book Towards a Theory of Neuroplasticity (2001), Christopher Shaw and Jill McEachern argue:

“Given the central importance of neuroplasticity, an outsider would be forgiven for assuming that it was well defined and that a basic and universal framework served to direct current and future hypotheses and experimentation. Sadly, however, this is not the case. While many neuroscientists use the word neuroplasticity as an umbrella term it means different things to different researchers in different subfields …”

Does neuroplasticity refer only to cerebral “form” uniquely as configured by changes in synaptic connections, or can we take neuroplasticity more literally, referring to the “squidgy” quality of the brain, capable to take new forms when the skull changes shape, for instance, or when a foreign object or tumour appears in the brain? How do we measure neuroplasticity?: do we watch rates of new neurons being made – neurogenesis – or are there other measurements?

These are all questions we will be exploring in this project.

PLASTIC PHILOSOPHY

The contemporary French philosopher Catherine Malabou is becoming known as one of the most important voices in current continental thought.

Malabou’s central philosophical concern is plasticity, which she develops across her interdisciplinary interests in philosophy, psychoanalysis, and neuroscience, although Malabou’s plasticity also enjoys detours through anthropology, art theory, literary criticism, gender and queer studies, and many other domains.

For Malabou, plasticity names the ability of something to give form and take form. Malabou argues that scientific discoveries, particularly in neuroscience, show that biology and thus life itself is plastic, and that we should take these discoveries as a cue to think about the mutability of many of the structures we previously assumed to be fixed.

Philosophy is now revealed be plastic, mutable and open to change. Science is plastic. Gender and sexuality are plastic. Economy is plastic. History is plastic.

Crucially, however, for Malabou plasticity does not equal an unlimited capacity for metamorphosis. Plasticity is not elasticity. Plasticity is not fluidity. Plasticity is not adaptability. Plasticity is not polymorphism.

For instances, Malabou criticizes certain neuroscientific conceptions of plasticity for confusing plasticity with endless adaptability.

For Malabou, the confusing plasticity with adaptability – the brain can heal after anything, can adapt to any task – shows neuroscience to have fallen prey to capitalist ideologies which attempt to use the brain as the metaphor for the perfect worker.

In relation to victims of cerebral trauma or injury, Malabou argues that neuroplasticity might also be conceived in destructive terms; a person might become irrevocably transfigured or changed following trauma, “destructive plasticity” having taken the place of “healthy plasticity”, creating new forms out of the annihilation of old ones.